The artworks featured in this post look best on larger screen sizes. To get the optimal visual experience, view this page on substack.com (not in your email) on a desktop or laptop computer.

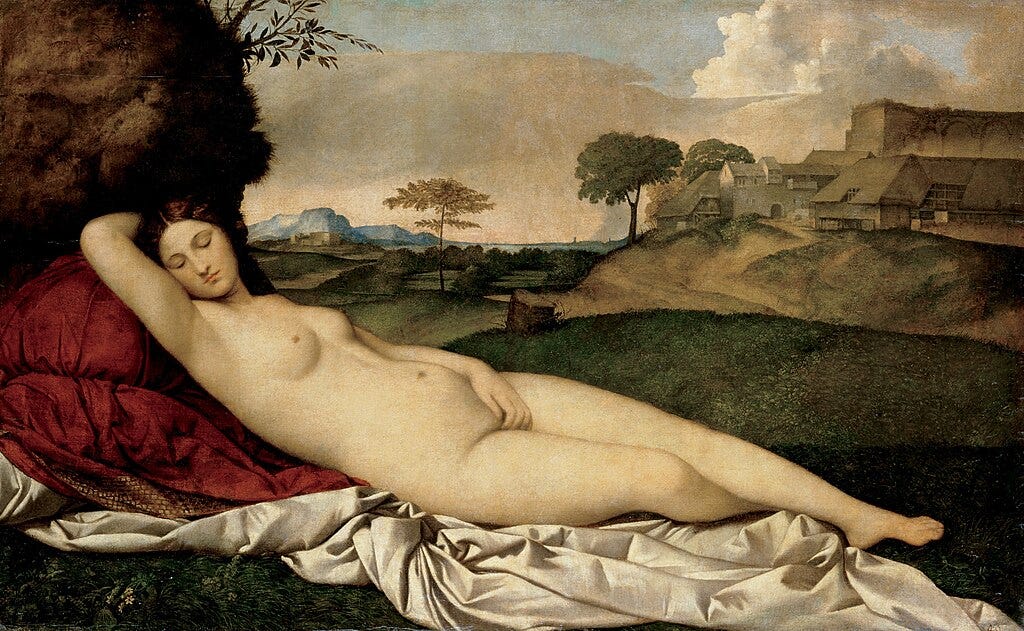

A naked young woman reclines elegantly on what looks like a bed — or a chaise lounge, perhaps? It’s hard to tell from the swirl of black and white bed sheets, which paradoxically look both sumptuous with their silky lustre yet almost monastically austere in their stark hues.1 The first of many paradoxes to come.

The deep dark sheen of the top sheet makes the woman’s skin pop, its undulating curves and pearly luminescence her only adornments. No clothing, jewellery, decorations or household items compete for our attention or point to her identity. She is bare and unforthcoming, much like the plain wall in front of her.

The woman’s face doesn’t tell us who she is, either. Her back is turned, leaving us with nothing but a vague reflection more akin to a dream vision than a mirror image. Who might she be?

Our only clue is the little boy propping up the mirror. Of course, he’s not a real boy: His wings betray him. He is Cupid, the ancient Roman god of erotic love. We don’t see Cupid’s token bow and arrows, but the pink ribbons entangled on his wrist allude to his other tools of the trade: a blindfold or else the shackles with which he binds the hearts of lovers.

So, the mystery nude can only be Venus, goddess of love and Cupid’s mother. The pair have traditionally been portrayed together since Antiquity. Case solved?

Not quite.

Venus — or Jane Doe?

Surely the painting’s title — The Rokeby Venus — settles the issue? Nope, sorry. The moniker is relatively recent and traces its origins to Rokeby Park, a country house in North East England, where the canvas hung for most of the 19th century.

The painting itself is a couple of centuries older, dating back to ca. 1647-51. Since then, it has also been known as The Toilet of Venus, Venus and Cupid and Venus at Her Mirror.

But the earliest known record of its existence, a 1651 household inventory of the Spanish painter and art dealer Domingo Guerra Coronel, lists it simply as “una muger desnuda” — a nude woman. No mention of any Venus.

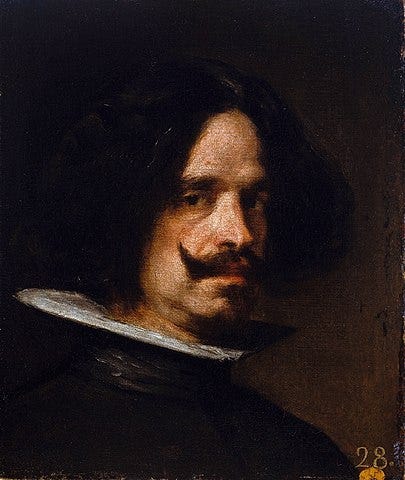

What about the author, Diego Velázquez (1599-1660), the most celebrated painter of the Spanish Golden Age? Did he provide an explanation as to the identity of his subject?

Again, nope.

Kings, nudes and outlaws

Today The Rokeby Venus is among Velázquez’s most revered works, but that wasn’t always the case. The painting only became known to the general public after its first display at the National Gallery in London in 1906. Before that, it had hung in obscurity for more than two centuries, hidden from prying eyes in the private collections of a string of grand homes in Spain and England.

The painting’s subject had a lot to do with its relative obscurity. The Rokeby Venus is Velázquez’s only surviving female nude (there may have been three more), and even that would have been one too many in his time.

Nudity, and especially female nudity, was almost unheard of in 17th century Spanish art. No Spanish painting from the 1630s-40s shows a woman with exposed breasts. Even bare arms were rarely shown, and mythological characters like goddesses, nymphs and sibyls were always chastely draped.

And no wonder. Any show of skin was met with raised eyebrows — to put it mildly — by the Catholic Church and the Inquisition. It was illegal to paint, import or own nudes, with offenders risking excommunication and exile.

This attitude towards nudity was unique among Western Europeans at the time. It continued, albeit with some loosening of morals, well into the mid-18th century when The Rokeby Venus, then part of the collection of the Dukes of Alba, wasn’t hung up due to its subject.

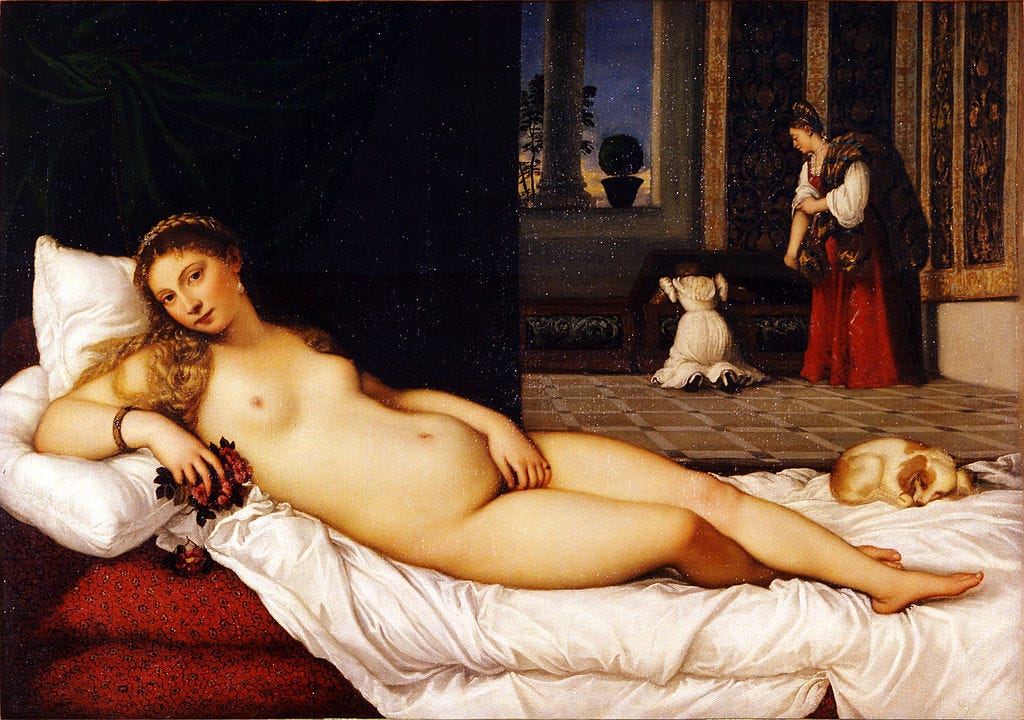

Of course, the Church turned a blind eye when it came to the rich and powerful and tolerated nudes as long as they weren’t displayed in public and portrayed mythological subjects. The collection of King Philip IV boasted some of Europe’s finest nudes, including canvases by Flemish and Italian painters like Rubens and Titian.

Velázquez, as court painter, would have had access to the royal collection. He was therefore familiar with the conventional pictorial representation of Venus at the time: either sitting upright and gazing at a mirror — commonly known as Venus at her toilet — or reclining on a couch or a bed.

In a clear departure from tradition, Velázquez has merged the two tropes in The Rokeby Venus. But what’s more interesting is that his Venus sports none of the usual mythological paraphernalia — jewellery, finery, roses or myrtle — that would undoubtedly identify her as the goddess.

The background isn’t a sumptuous palace setting or a sprawling Arcadian landscape, either. You know, the natural habitats of goddesses. All we see here is a bare wall in what looks like a perfectly ordinary, contemporary room. The woman wears her hair in a simple modern style rather than an ornate updo, and she’s a brunette — yet another break with tradition.

For all we know, she could be a mere mortal.

Hiding in plain sight?

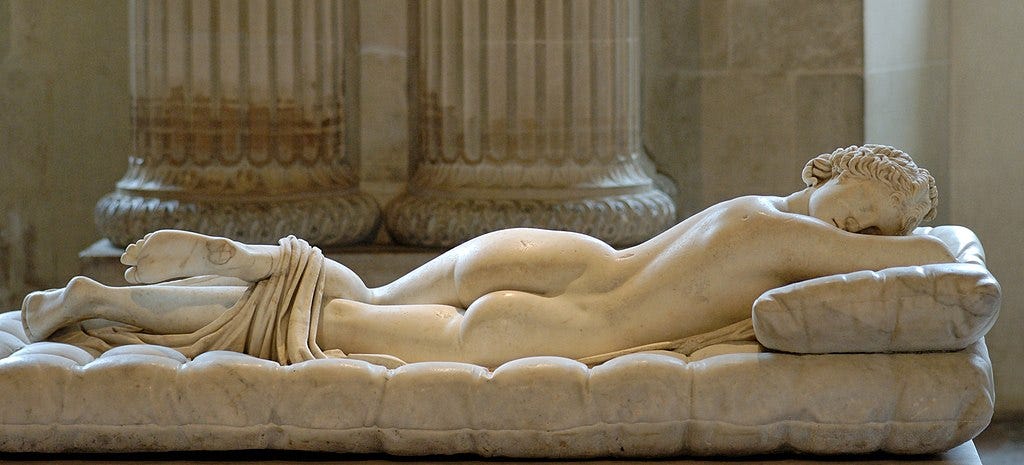

Another innovation of The Rokeby Venus is the back view of its subject, which is highly unusual for the time period. There were much older precedents in classical sculptures, such as the Borghese Hermaphroditus, of which a cast was made for the royal collection and was known to Velázquez.

The art historian Peter Cherry has suggested that Velázquez opted for a back view to avoid censorship. A view from behind, however tantalising, might have been less scandalous than full-frontal nudity.

Still, why would Velázquez go to all this trouble and pander to modesty requirements if, at the same time, he didn’t provide clear pointers that the female figure is indeed Venus? A goddess in the nude might elicit a modicum of reverence or spiritual awe, but the back view of an anonymous naked mortal is something else altogether.

And then we have the obfuscation of the face. It isn’t helping.

There’s no doubt Velázquez went to some lengths to ensure his subject wasn’t an identifiable person. The blurred reflection is a deliberate artistic choice. We know he was perfectly capable of painting clearly and crisply, as is evident in this very painting. The woman’s body is bright and focused, with hardly any visible brushstrokes — almost like photography.

Yet the face is blurred.

What’s more, Velázquez initially painted the woman’s head so that her nose was visible but subsequently changed his mind.

All that begs the question: Why hide the face of a goddess? Is she Venus, really, or a mortal woman rather poorly disguised as the deity? Was she someone Velázquez knew?

What we know so far

The Rokeby Venus remains shrouded in mystery. We’re not sure when or where the painting was made. It has been variously dated to before, during and after Velázquez’s second and last visit to Italy (1649–51).

Portrayals of Venus from a back view with her knees tucked were a common erotic motif in ancient sculpture, so it’s likely Velázquez would have seen some examples in Italy — but there were casts in Madrid as well.

The general consensus is that The Rokeby Venus was painted from life, which is another indication it may have been made in Italy. Rome was a far more liberal city than Madrid at the time. While it was acceptable to employ male nude models in Spain, female nude models were frowned upon.

Velázquez’s technique, with its strong emphasis on colour and tone, also suggests the work is from his mature period.

We don’t know who The Rokeby Venus was painted for, either. If it is truly a mythological painting by the king’s painter no less, surely you’d expect to see the canvas in an inventory of the royal court or at least that of a high-ranking aristocrat. Instead, this Venus first shows up in the inventory of a minor painter and art dealer in Madrid and was only later purchased by Gaspar Méndez de Haro, 7th Marquess of Carpio.

That first inventory makes no mention of Velázquez’s name, either — to avoid censorship, perhaps, or some other kind of scandal? Some claim the unknown model was a mistress Velázquez had in Italy and that they had a child together.

Others believe the model is the same as in Velázquez’s Coronation of the Virgin (1642). Judge for yourself:

The Venus effect

Ultimately, Velázquez’s Venus poses more questions than it answers. Her mystery is just as, if not more, seductive than her curves. We are lured not by what’s on display but by what’s concealed — and by what we are imagining.

When we first see her, she looks almost as if she’s about to turn around and face us. Yet she doesn’t. We then try to make her features out in the mirror, but she dissolves again.

Is she a goddess or simply a beautiful woman? A real person or an allegory of erotic love, seduction and ideal beauty? Velázquez leaves it to us to fill in her features and construct her identity, making her exactly who we want her to be.

Not only is the image in the mirror blurred, but it is also an illusion. This is known as the Venus effect, a phenomenon in the psychology of perception. It’s physically impossible for Venus to be looking at herself in the mirror and for the viewer to see her reflection. As we are not directly behind her, what she sees can’t be the same as what we see.

It would be more accurate, therefore, to conclude that Venus is gazing at the painter’s reflection. Or, now that she hangs at the National Gallery for all to see, at our reflections. She sees and is being seen, the male gaze locking eyes with the female gaze.

Reflection, gazing, reality and illusion are recurring themes in Velázquez’s work. They also appear in his masterpiece Las meninas (1656), where a mirror on the back wall reflects the images of King Philip IV and his wife, Queen Mariana of Austria, and Velázquez himself stares straight into the viewer’s eyes.

And so, “the most beguiling back in the history of Western art”, as Geoffrey Smith puts it so eloquently, straddles — and perhaps erases — the boundary between the male and the female gaze, the seducer and the seduced, the spiritual and the corporeal, the sacred and the profane, the intimate and the public, the personal and the mythological, the illusory and the real, the hidden and the revealed.

The Rokeby Venus is a contradiction in terms, an elegant subversion of societal norms and morals and of our preconceived notions. Like all great art, it stops us in our tracks and cuts open the fabric of reality — only to reveal other, deeper truths glowing through the cracks.