On living fast, dying young and the badass Princess of Éboli

Or: nuns, widows & femmes fatales in sixteenth-century Spain

Ah, here you are! Long time no read — mea culpa, I confess. But what are

seveneight months between friends? Come in, come in.Get settled, put your feet up and, if I may suggest, pour yourself a cuppa of your stimulant of choice. Or something stronger, perhaps, if the hour and your constitution permit.

A glass of Spanish red would be most fitting, for I’m about to introduce you to a most dangerous woman, if we are to believe her enemies — and we must always grant our enemies such courtesy for giving us the time of day.

Dangerous or not, she certainly was the ‘most notorious Spanish woman of the sixteenth century’.1 And mind you, that was no ordinary century.

Setting the scene

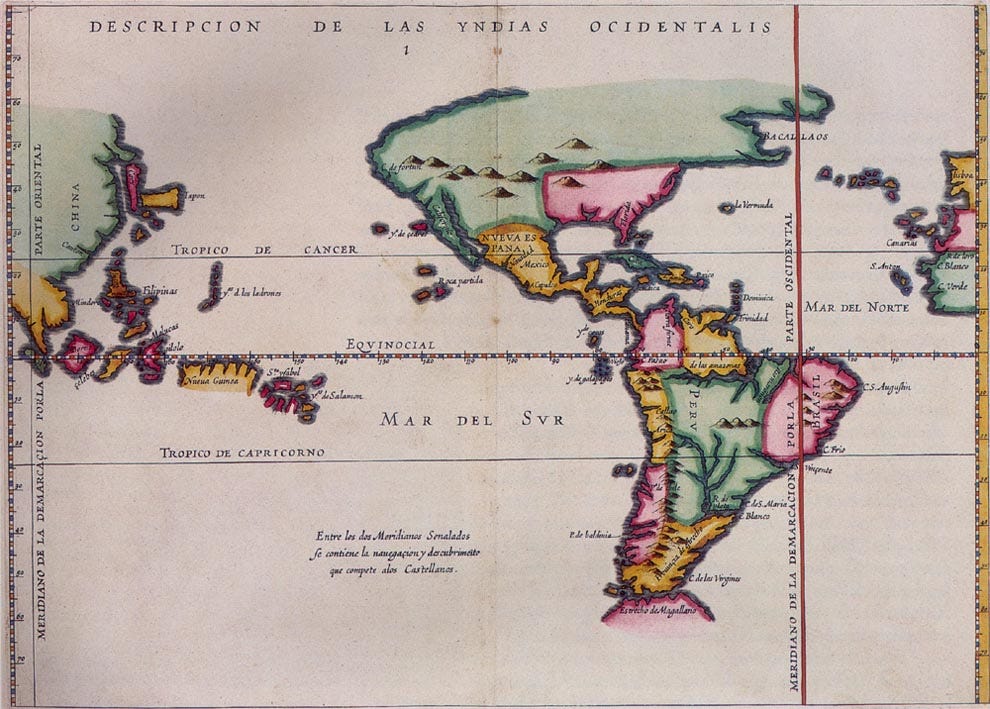

The 1500s (and 1600s) were the golden age of the Spanish Empire; a time when Spain, along with Portugal, led the vanguard of European maritime exploration. Those weren’t just the powers that be in their allotted corner of the continent: The two countries were arguably the first-ever global superpowers, so much so that they signed a treaty in 1494 literally dividing the world between them.

Merchants charted new trade routes across oceans, colonial outposts sprouted like grass and untold riches flowed towards the palaces and coffers of Iberia as working-class boys from Granada to Madrid dreamed of becoming the next Columbus.

Soon enough, some of the newly minted wealth started trickling down the social ladder ushering, among other things, a revolution in the arts and letters. It was the century of Cervantes and Lope de Vega, of Velázquez and El Greco.

In short, it was a grand time for Spain, and a pretty terrible time for the Americas.

Enter: our leading lady

I make this historical detour because none of us can help being men and women of our time, regardless of how progressive or unorthodox we imagine ourselves to be.

Our subject was born and bred against the illustrious backdrop of sixteenth-century Spain, and this likely explains many of the choices she made later in life.

As a daughter of the uppermost echelons of the Spanish upper class, for all she knew, by God’s grace her kind ruled Spain, and Spain ruled the world. How else was she to go through life if not with panache, hubris and high treason?

But I am getting ahead of myself. It’s about time you two were introduced.

Here’s the devil herself: Please meet Doña Ana de Mendoza de la Cerda y de Silva Cifuentes, Princess of Éboli, Duchess of Pastrana, II Princess of Mélito, II Duchess of Francavilla and III Countess of Aliano — better known as Ana de Mendoza or Ana, Princess of Éboli.

Let me guess. The first thing you noticed was the patch over her right eye. What’s that all about?

Explanations vary. According to some accounts, the young Ana lost or damaged her eye in a fencing accident. Others propose that the patch was just an accessory and an effort to appear sexy’. (?!) Still, the most authoritative evidence from the time is that she likely had a degenerative eye disease.

At any rate, while Ana did manage to turn her physical impairment into an iconic fashion statement, that’s the least interesting thing about her. For there’s so, so much more to her.

The woman and the myth

The Princess of Éboli has become the stuff of legend, making it hard to tell the woman from the myth.

Depending on who recounts Ana’s story, she is either the quintessential femme fatale, a lover, bane and murderess of powerful men — or a tragic feminist heroine, a bright and courageous woman ahead of her time, oppressed and unjustly ruined by a misogynistic system — or an inept and shallow spendthrift who squandered her family estates through vanity projects and luxurious living — or something of a madwoman, a whirlwind of volatile mental health, fraught relationships and irrational lifelong grudges with disastrous consequences for all — or a cunning political actor at the highest level and co-conspirator accused of high treason.

The Princess of Éboli also appears in numerous works of fiction, most notably in Schiller’s play Don Carlos and Verdi’s opera of the same name, where she plays the baddie who has ensnared King Philip II. Here is the legendary Maria Callas singing the Princess of Éboli’s aria ‘O don fatale’:

Legends and romance fiction aside, even her contemporaries couldn’t make their minds up about her, dubbing her everything from the factual la tuerta (‘the one-eyed one’) through the derogatory la puta (‘the whore’), Jezebel and la hembra (‘the female’ or ‘that woman’) to the loving la canela (‘the cinnamon’).2

Ana didn’t mind one bit, apparently. She seems to have been something of a public relations and marketing mastermind. The princess enjoyed the gossip surrounding her and played an active part in the crafting and control of her image.

And my oh my was the gossip juicy.

She was rumoured to have had passionate affairs with both Philip II and his trusted royal secretary, Antonio Pérez.

Her difficult personality was said to have led to the scandalous closure of a convent founded by none other than Teresa of Ávila — the future Saint Teresa de Jesús, a prominent Spanish mystic and religious reformer.

Ana has also been dismissed as a failure of a duchess whose incompetence and unhinged spending ruined her estates after her husband’s death.

Most notoriously, the 39-year-old Princess of Éboli was arrested in 1579 for her alleged involvement in the murder of Juan de Escobedo, secretary of the king’s half-brother, Juan of Austria — one of her many purported attempts to meddle in state affairs. She remained imprisoned until her death 13 years later.

Let’s take a closer look at her fascinating life and try to separate fact from fiction.

Ana’s not-so-humble stock

If ever there was anyone who came to this world with a silver spoon in their mouth, it was Ana. She was born in June 1540 in the sleepy town of Cifuentes in central Spain. Cifuentes was the heart of the estates of the Silvas, the family of her mother Catalina, daughter of Fernando de Silva, IV Count of Cifuentes.

Catalina had married Diego Hurtado de Mendoza y de la Cerda, II Count of Mélito and grandson of the hugely influential Great Cardinal, Pedro González de Mendoza, also known as the Third King of Spain alongside the country’s most renowned monarchs, Isabella I and Ferdinand II.

This fact alone should tell you that the Silvas and the Mendozas weren’t your garden-variety aristocrats. They were among the wealthiest, most powerful, well-connected and cultured families of sixteenth-century Spain.

As if that weren’t enough, Ana was a rare breed — an only child — making her the richest and most coveted heiress in the realm. And, as an added bonus, she was quite the looker. Contemporary accounts describe her as ‘very pretty, although on the small side’.3

A house divided against itself

Now, before you get too envious, I hasten to add that for all her privilege and finery, the Princess of Éboli had a nightmare of a childhood.

Her mother, for one, was ‘a woman of malicious and mean temperament, and a bit of a liar besides’.4 The string of adjectives goes on: ‘authoritarian’, ‘violent’, ‘irascible’, short-tempered, disobedient, imprudent.5 Catalina is also said to have been a gossip and incapable of managing the household and spending sensibly.

As for Ana’s father, ‘the only thing that [he] … seems to have inherited from his illustrious grandfather, the Great Cardinal, was a liking for pretty young females’.6 Diego squandered fortunes on his lovers, and his shenanigans were the constant talk of the court.

Here’s just how bad it was: Shortly after Ana’s birth, her father attended the funeral of a relative… and left the dead man’s daughter pregnant!

Diego’s weakness for the fair sex didn’t diminish with age. In the mid-1550s, he had an affair with a lady-in-waiting at court while his wife and heavily pregnant daughter were living at the very same royal palace in Valladolid. The exasperated Ana and Catalina pleaded with the Regent, Princess Juana, with Catalina threatening to sue for a divorce — a most scandalous and ungodly thing at the time — and the philanderer was promptly sent away from court.

As for Diego’s skills as a statesman, well, let’s just say no one was impressed. His title and connections landed him various sinecure posts, but those were handed out mainly to keep the man occupied and as far from court and his family as possible.

Ana wavered between love and hatred for her father in her younger years but in the end despised him wholeheartedly. In 1576, shortly after Catalina’s death, Diego announced his sudden marriage to the young Magdalena de Aragón, hoping to sire a son and disinherit his daughter. The plan didn’t work. Diego died in 1578, Magdalena gave birth to a stillborn daughter soon after and henceforth had to rely on Ana’s generosity to meet her basic needs.

Ana’s relationship with her mother was no less fraught, so when an opportunity presented itself to leave her parents’ household — ‘a hellhole of hatred, persecution, calumnies and even penury’7 — she welcomed it. That opportunity, of course, was marriage.

More than skin deep

Young, rich, pretty and titled to the nines, the Princess of Éboli was also quite bright. Contemporaries would often remark upon her maturity and sensibility for someone so young — and for someone from her family.

According to Princess Juana herself, Ana was ‘the prettiest thing in the world’ and ‘more intelligent than all of them’ (referring to Diego and Catalina).8 One Doña Leonor Manuel, likely a lady-in-waiting at court, wrote that the girl was ‘very honourable and intelligent […], and she seems to be much more mature than her years’.9

Ana wasn’t just naturally bright: Her intelligence had been cultivated. She was one of the best-educated women in Spain, and probably in all of Europe. Like most noble girls of her time, she’d received a basic education and likely quite a bit more — at home, possibly aided by a private tutor and with the substantial input of her mother, as was customary.

You see, the myth of the illiterate or barely educated noblewoman, in sixteenth-century Spain at least, is precisely that — a myth. Boys of noble stock weren’t the only ones who were educated; so were most girls, and for very good reason.

Spain waged nearly incessant wars in the 1550s. Noble sons often died young in battle, leaving behind a widow and small children. Once the husband died, his estates passed to his wife until — and if — she remarried. It was then her legal duty to bring up and educate her children, negotiate strategic marriages for them, assure the continuance of the title and run and preserve the estates that one day her eldest son would inherit.

Aristocratic parents expected their daughters to assume responsibility for themselves and their children at some point and brought them up accordingly. From birth, girls were trained to be not just wives and mothers but also widows. As is often the case in history, death was the great equaliser between the sexes, and the line of oppression in reality ran not so much along divisions of gender but more along those of class.

At a minimum, Spanish noblewomen were literate, numerate and fluent in Latin. Their education likely included aspects of law, finance and politics as well, for many widows proved to be excellent estate managers, litigators, negotiators and politicians.

As an only child and heiress to two of the country’s most illustrious families, Ana must have been trained to forge her path in the world accordingly. Her correspondence reveals she could not only read and write but did so with eloquence and style — ‘a powerful, individual female voice’.10

She wasn’t all prim and proper, though, and didn’t shy away from common phrases, idioms and vulgarities. Diego himself commented that his daughter could ‘swear like a trooper’.11 Ana didn’t seem especially bothered about her penmanship, either: Her handwriting was ‘an absolute nightmare’.12 King Philip II, ‘not himself the possessor of the most legible hand in Spain,’13 would moan about the impossibility of deciphering her missives and had to have them transcribed.

Family tradition must have influenced Ana’s education as well. The House of Mendoza boasted a rich cultural inheritance that could be traced as far back as the fourteenth century. Famed for their learning, their interest in and patronage of the arts, their palaces, churches and university colleges, the Mendozas had played a pivotal role in introducing the Italian Renaissance in Spain and even had several renowned writers and poets in their family tree.

The Silvas, Catalina’s family, were no less cultured. Whatever the content of her character, there is no doubt Ana’s mother was among the most learned women of her time. Alvar Gómez, a Professor of Greek in Toledo, praised her as ‘a most brilliant woman who sheds light on learning and frees the feminine sex from darkness’.14

Catalina’s personal library, which the young Ana must have read from, numbered a whopping 288 titles plus a substantial number of folio volumes in Spanish, French, Italian, Greek and Latin. Those included the classics, works of history and politics, legal texts, books of devotion, novels of chivalry and other works of fiction as well as various educational works like dictionaries, grammars, books of music and books of quotations. Bear in mind that the average library at the time was between 70 and 100 titles and books cost a fortune.

So, yeah, the Princess of Éboli was one smart cookie indeed.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single woman in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a husband.

Ana was such an eligible prospect on the marriage mart that Prince Philip himself, not yet king at the time, personally arranged her match.

Her betrothed? Ruy Gómez de Silva, a minor Portuguese aristocrat. He’d initially come to Spain as a page of Empress Isabel, the prince’s mother, but quickly became a cherished companion to the young Philip, 11 years his junior.

Over time, the former page came up through the ranks to become a member of several government councils. Yet his most coveted post was arguably that of Sumiller de Corps, the head of the prince’s household in charge of his innermost rooms and most intimate needs.

Of his job, Ruy Gómez would coyly say that it was to ‘help dress His Highness’,15 but in truth he had Philip’s ear and was the first and last person he spoke with each day. His influence in court was such that foreign ambassadors referred to him, half in jest, half in earnest, as ‘Rey’ (King) Gómez.

So, why did Diego and Catalina agree to marry Ana, not yet 13, to the 36-year-old Ruy Gómez? (Yikes.)

First, because the prince had said so.

Second, because Ruy was actually quite the catch. Through this marriage, Ana’s family hoped to win to their side the future king’s trusted counsellor and clear favourite — a major coup for the Mendozas and a strategic blow at their archenemies, the House of Toledo, headed by the formidable III Duke of Alba.

Besides, the prince sweetened the deal by promising the young couple 6,000 ducats in annual rents — nothing to sneer at even by Mendoza standards — and, as a special gesture of goodwill, travelled to attend the ceremony.

The marriage was celebrated in 1553 with both the bride and groom present, but on the condition that it would not be consummated until at least two years had passed due to Ana’s age.

Shortly after the ceremony, the groom left with Philip to England for his marriage to Mary Tudor and then on to Flanders. Ana stayed with her parents.

Affairs of state would keep Ruy abroad for the next four years, save for a short visit home in 1557 that left Ana pregnant. She had their first child, Diego, in April 1558, and her husband returned for good in 1559.

Wife, mother, mistress?

Things were looking up for Ana, or so it seemed at the time. She was freed from her toxic parents at last, and by all accounts her relationship with Ruy appears to have been a very happy one, the arranged marriage and 24-year age gap notwithstanding. The two were also the undisputed power couple at court, arguably second only to the king and queen themselves.

But then one day, tragedy struck. Little Diego, not yet two years old, died after an accidental fall from the arms of a nursemaid. That likely caused Ana, pregnant again, to have a miscarriage.

The couple eventually recovered from the shock and went on to have two more children: Ana, born in 1561, and their now eldest son and heir, Rodrigo, born in 1562.

Rodrigo’s appearance seems to have raised a few eyebrows. Rumour had it that he was the secret love child of Ana and Philip II — all because the boy had fair hair, unlike both his mother and Ruy.

However, there is absolutely no evidence that the king and the Princess of Éboli were ever involved. By all accounts Ana and Ruy were happily — and prolifically — married. They had a total of nine, possibly ten children, six of whom survived to adulthood. After Rodrigo came in quick succession Pedro (1563, died 1571), Diego (1564), Ruy (1565), María (1566, died 1567), Fernando (1569) and Ana (1572).

The only time any hanky-panky could possibly have occurred was between 1559, when Philip and Ruy returned from the Low Countries, and 1569, when Ana and Ruy relocated from Madrid to Pastrana.

By the time the king returned to Spain in 1559, Ana was already or soon to become pregnant with the child she miscarried. She remained in an almost constant state of pregnancy for over a decade. This alone renders her a most improbable target for the advances of the king, who could have any young, attractive, single and positively unpregnant lady in Spain had he wished to.

That’s not to say Philip didn’t have mistresses — he did, on and off, mostly when between wives (of which he had four). In the early 1560s, he had an affair with one of his sister’s ladies-in-waiting, but she was sent away and swiftly married, presumably to a man who didn’t ask too many questions.

In October 1564 Ruy Gómez himself informed the French ambassador that the king’s extramarital relations ‘have almost all ceased, such that everything is going so well that one cannot ask for more’.16 The king seemingly spent the rest of the decade smitten with his young bride, Elisabeth of Valois, whom he loved dearly.

We also shouldn’t forget Philip’s keen support for the marriage between Ana and his favourite counsellor and dear friend. For her part, Ana became one of Queen Elisabeth’s closest companions and lived at her court for the entirety of her marriage to the king (from 1559 until the queen’s death in 1568).

All in all, ‘it would have been the height of madness for [Philip] to initiate relations with Ana’.17 Unless, of course, the forbidden fruit proved all too sweet.

Yours, Sister Ana

Now, let’s examine Ana’s thorny relationship with Teresa of Ávila, the future Saint Teresa de Jesús best known for the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. The Princess of Éboli has traditionally been painted as the villain in the whole affair, but later historians such as Trevor J Dadson beg to differ.

During the sixteenth century it became customary for Spanish noblewomen to found convents and monasteries. They footed the bill for the establishment and upkeep of religious institutions, and often provided the buildings themselves.

There’s no such thing as a free lunch, of course, even in matters of faith, so a patroness or benefactress expected certain favours in return.

For one, she expected ‘her’ convent to be her final resting place, with the nuns praying regularly for her soul and those of her relatives. Should her husband die before her, she also expected to be able to retire among the sisters, often temporarily and without taking the veil, so that she could grieve in a safe, female-only space.

This practice was especially prevalent in the reformed religious orders. Chief among those was that of the Discalced Carmelites led by Teresa of Ávila, who founded 17 convents in her lifetime.

All of Teresa’s early establishments were patronised by the sprawling Mendoza family. One such convent was set up in Pastrana in 1569 under the name of Sor Ana de la Madre de Dios, thanks to a generous financial injection courtesy of Ana and Ruy.

Little did they know that this project would end up staining the future saint’s otherwise spotless biography, to say nothing of Ana’s positively chequered one.

You see, the Pastrana convent was the only one established by Teresa to be subsequently — and scandalously — closed. And all the blame has been assigned to Ana, the wicked and stubborn Princess of Éboli.

Here’s how the events unfolded, according to Ana’s detractors. Shortly after Ruy’s sudden death in July 1573 — he was only 56 years old — the distraught Ana left Madrid with his coffin and entered the Pastrana convent. So far, her behaviour didn’t strike people as odd: She was going to bury her husband and grieve him for a (short) while before returning to the world, her family and her estates.

But then, to everyone’s shock, Ana started calling herself and signing documents as Sor (Sister) Ana de la Madre de Dios. Even more outrageously, she outright refused to assume her legal duties as guardian and tutor of her six minor children, aged between one and 12, brazenly disregarding the constant admonitions from her relatives and the king himself. People started thinking she’d gone mad.

And then it got worse. Initially Ana was lodged in an austere cell, just like the other convent inhabitants. But it didn’t take long before the princess, accustomed to a very different lifestyle, grew tired of the cell — so she just upped and moved to a separate house in the convent garden, with her maids in tow. The house had closets installed to store Ana’s fancy dresses and jewellery and, more importantly, had direct access to the street, allowing her to come and go at will.

Such liberties didn’t sit well with the ascetic Teresa. The two women, neither of whom was used to taking orders, had already locked horns more than once. Ana’s move to the garden house seems to have been the final straw, prompting Teresa to order all nuns to abandon the convent and leave Ana and her entourage alone. Eventually the princess returned to her palace in Madrid, and the convent closed for good in April 1574.

The whole affair has been seen as further damning evidence of Ana’s difficult personality and fickle mental health. But that might not be entirely fair.

What we know of Ana’s stint in the convent comes almost exclusively from Teresa’s biographers and other biassed sources. Aided by the benefit of hindsight and motivated by a desire to paint the saint in a positive light, they needed a scapegoat to justify the closure of the Pastrana convent — Teresa’s only failure.

Who else could be at fault if not the notorious Ana de Mendoza, the Princess of Éboli, already famed in her lifetime for being headstrong and not one to bite her tongue? Her subsequent arrest and imprisonment further cemented her villainous reputation and lent credence to the Teresian faction.

Yet, if we consider Ana’s circumstances and the religious and social customs at the time, there was nothing particularly unhinged or stubborn about her behaviour. She was following a perfectly conventional pattern whereby bereaved patronesses entered their convents on a temporary basis to mourn hidden from prying eyes.

And there was much to mourn. Not only had Ana loved her husband dearly, but she was only 33 years old with six young children to bring up, educate and marry off, all on her own. She knew nothing of the running of the family estates.

What she did know was that Ruy had left exorbitant debts equivalent to 285,179 ducats — at least four times the annual revenue of the richest noble estate in the realm — which took her until 1579 to pay off.

In light of all that, Ana’s hesitation to step into her new role, while unorthodox, certainly made sense. As soon as she accepted the legal guardianship of her children, she’d be personally responsible for everything: the kids, the estates, Ruy’s debts. No wonder she needed some time to come to terms with it all!

But what of Teresa? What could possibly have caused the huge rift between Ana and her? Nothing indicates the princess intended to stay in the convent permanently, so surely her finery and separate lodgings (and potentially exasperating presence) could not have been that big of an affront to the future saint. Was their personality clash that insurmountable?

While you can bet the Princess of Éboli wasn’t the easiest of tenants, Teresa might have had other, more unsavoury reasons for abandoning both Ana and the convent.

You see, the Mendozas and the Ébolis had patronised Teresa’s early projects, but from the late 1560s she’d started inching ever closer to their archenemies, the Albas. Her keen political nose had rightly sensed the Ébolis’ waning influence at court, as the intolerant and authoritarian policies pushed by the warmongering Duke of Alba gradually won favour at the expense of Ruy’s preference for a decentralised and compromise-oriented system.

So, from 1571 onwards, all of Teresa’s convents were founded courtesy of the Albas. The first one opened without pomp or propaganda; she probably wanted to keep a low profile in the beginning.

But by 1574, with Ruy dead, the Pastrana convent closed and Ana disgraced and possibly mad, there was no longer need for secrecy. The Ébolis were done for, and Teresa could openly jump ship from Mendoza to Toledo. That was no doubt a sensible political decision, but it does raise a few questions about her Christian morals.

A one-woman army

Ana might have taken a while to emerge from her seclusion, but once she did, she wasted no time mucking about.

Her first order of business was to arrange the marriage between her eldest daughter, Ana, and the Duke of Medina Sidonia in February 1574, a big political win for the Ébolis. The young Ana would go on to become a very successful duchess in her own right — one of her granddaughters, Luisa María de Guzmán y Sandoval, even became queen of Portugal.

For the most part, the Princess of Éboli didn’t fail the rest of her children either. Aged between one and 11, they lived with their mother, first in Pastrana (1573–1576) and then in Madrid (from March/April 1576 until Ana’s arrest in 1579). During all those years she was responsible for their upbringing and education, and the later course of their lives suggests she did a pretty good job.

The eldest son and heir, Rodrigo, died relatively young in battle but did leave behind a noteworthy personal library. He also ensured that his eldest son, Ruy Gómez, would be tutored in Brussels by the great Justus Lipsius, a Flemish Catholic philosopher, humanist and philologist famous for reviving classical Stoicism in a form compatible with Christianity.

Diego, his mother’s favourite, grew up to be a successful politician, landowner, courtier and renowned poet.

Ruy became a commander in the Order of Calatrava and was made Marquess of Eliseda by King Phillip III.

Fernando took holy orders and became a prominent churchman. He was Bishop of Sigüenza, then Archbishop of Granada and finally Archbishop of Zaragoza.

The youngest sibling, Ana — presumably the Ébolis had run out of names by this point — sadly got the short end of the stick as she ended up accompanying her mother in her various imprisonments.

In addition to securing her kids’ future, the widowed Princess of Éboli had to keep the wolves away from the family fortune. She is traditionally portrayed as an incompetent estate manager at best, and at worst as a spendthrift whose love of luxury ended in financial ruin.

That was certainly Rodrigo’s assessment — so much so that he pleaded with the king to take control of the estates away from his mother. It must be said, though, that as the eldest son and heir he had a clear conflict of interest, so perhaps we ought to take his claims with a pinch of salt.

In fact, the hundreds of documents signed by Ana during her widowhood — dated from July 1573 right up to the last months of her life in 1592 — paint a different picture.

While Ana took full control of the Pastrana estates and ran them personally for some six years until her arrest in 1579, she did retain most of her husband’s expert advisers (officials, accountants, secretaries) and largely heeded their counsel. On occasion she’d put her foot down and express her own views, but, to her credit, none of these seem to have been detrimental to the estates.

She tried to manage her affairs and salvage the estates even during her imprisonment, when most of her legal powers had been stripped and her possessions — embargoed. Notaries would come to her cell so that she could sign the necessary documents.

Overall, the Princess of Éboli’s career as an estate manager is further evidence for her education and intelligence. Her legal and financial dealings show that she was a capable administrator who took her duties seriously.

As for her debts and love of luxury, well, that was the mark of the highborn. Ana certainly had a penchant for fine clothes, furs and jewellery and received many such gifts from her friend, Queen Elisabeth. If you were to take a stroll along the streets of Toledo in the 1570s, you might have spotted the princess prancing around donned in the hottest French fashion, complete with a hat and a hairdo à la française.

But so did all noblewomen (and men!) of the period. All showered themselves in finery; all spent much more than they earned; all had mortgaged their estates to the hilt. It was the done thing. Had Ana been frugal, she would’ve stood out and quite possibly faced reproach and ostracism for not following social convention, as we saw with her stint at the convent.

Ana was also very conscious of her image and the soft power it afforded her. Status markers matter, and they mattered a great deal back then. She likely felt she had to carry herself in a certain way; a way that suited a Mendoza. In later years, when her relationship with the king had started to sour, she’d remind him repeatedly that she was a Mendoza, and what that meant.

Plus, with her parents and husband gone, she alone represented the family, the Éboli faction at court and her children’s interests, making it all the more important to look powerful, formidable, ostentatious — especially as a female in a society ruled by and heavily biassed towards men. As we’ll see later, at least some of Ana’s legal dealings left her feeling that she was unfairly penalised for being a woman.

Friends (with benefits?)

Antonio Pérez del Hierro was Philip’s undersecretary of state for some 11 years and one of the most interesting figures of the period. He was also Ana’s downfall, and overall seems to have been trouble and bad news for many: his family, the king, his native Aragon.

The man had a talent for sowing wind and brewing conflict, often leaving it to someone else to reap the consequences: a trail of distrust, death and destruction. It’s either that, or he suffered a decades-long streak of catastrophic luck at a continental (quite literally) scale.

The second part of Antonio Pérez’s life especially is wilder than fiction. Choke-full of court intrigues, power struggles, arrests, revolts and insurrections, action-movie-level prison breaks, international military engagements, failed assassination attempts, borderline civil war, exile, espionage and trafficking in state secrets, it puts Game of Thrones to shame.

In between all this, Antonio even managed to attend the opening night of Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors, and his spell in London might have inspired the character of Don Armado in Love’s Labour’s Lost.

Do look him up if you have the time; it’s absolutely mind boggling that people used to live like this — that such biographies were at all possible. And mind you, that was the life of a civil servant, not some warlord, mercenary or pirate. Truly our most successful and impressive domestication has been that of our own species, never mind dogs and horses.

As a hereditary statesman — he was a natural son of Gonzalo Pérez, Secretary of the Council of State of Charles V of Spain — Antonio received solid training in matters of state, first under his father’s tutelage and later at some of the most esteemed universities of his time: Alcalá de Henares, Leuven, Salamanca, Padua, Venice. He was a gifted and shrewd politician, albeit of questionable moral fibre, and his writings were a significant influence on Spinoza a century later.

In 1568 Antonio Pérez was appointed secretary of King Philip II. During his first decade in the job, he had considerable influence over the monarch who valued his advice.

After Ruy Gómez’s death in 1573, Antonio spearheaded the Éboli faction at court and developed a close relationship with the widowed Princess of Éboli. The exact nature of their relations has always been a subject of much speculation and gossip. Between the two of them, they certainly had enough enemies who’d be keen to portray them as lovers, and many did provide circumstantial evidence to that effect.

The jury’s still out on whether Ana had an affair with the royal secretary. It’s certainly plausible of course. Antonio Pérez was around the same age as the princess, she’d known him for many years prior, and they had many shared interests: fine art, fine clothes and a fine scheme, not necessarily in that order. For all his faults, he was an interesting and intelligent man, and probably charismatic to boot, and very powerful for sure. It’s not too far-fetched to assume that a young and distraught widow with six small children to bring up, a behemoth of an estate to run and a mountain of debt to repay might like a strong male figure in her life.

But then again, Antonio was married and with children of his own (not that that’s ever stopped anyone). Also, he might have risen up in the world, but he’d always remain a lowly administrator of illegitimate, non-aristocratic and possibly converso origins, whereas the Princess of Éboli was one of the highest born in the land. Would the proud and status-conscious Ana deign to get involved with such a guy?

Antonio’s birth was additionally tarnished by the fact that his father, Gonzalo Pérez, was a priest whose enemies accused him of having fathered Antonio after his ordination.

Furthermore, some historians have suggested that Antonio might actually have been the natural son of Ana’s husband, Ruy Gómez, as Antonio grew up on his estate and benefited from his protection on multiple occasions. Gonzalo Pérez could have admitted his paternity under duress, as a personal favour to Ruy or out of Christian charity.

At any rate, whether theirs was a matter of love, lust, friendship or politics, what’s certain is that Ana and Antonio were allies and quite close indeed, and did meddle in state affairs.

Their scheming eventually embroiled them in a massive scandal that would be their downfall. But, as we’ll see below, Ana’s involvement in the whole affair has yet to be proved.

Whodunit?

Whatever the nature of Ana and Antonio’s relationship, it proved fateful for both. It resulted, in 1579, in her being imprisoned for life and him spending the next three decades alternately as a prisoner, a refugee or an exile; as a wanted man on the run or a traitor trying to eke out a living selling state secrets — and ultimately dying in abject poverty in Paris in 1611.

The cause of the duo’s fall from grace was the murder of Juan de Escobedo, the secretary of Philip’s illegitimate half-brother, Juan of Austria.

On 31 March 1578, Escobedo, returning from the Princess of Éboli’s residence, was stabbed to death in a dark alley in Madrid, allegedly by six hitmen hired by Antonio Pérez. The incident came hot on the heels of two failed poisoning attempts during meals at Antonio’s house on 8 and 12 March. I do wonder why Escobedo accepted that second dinner invite. Surely one case of bad stomach is enough for one week?

The scholarly consensus has always been that Antonio orchestrated the murder — on the orders of the king, as he’d claim later. It appears he obtained Philip’s consent by exaggerating and misrepresenting Juan of Austria’s activities in Flanders (then part of the Spanish Netherlands), his contacts with local rebels and the impact of his intended marriage to Mary I of Scotland.

Beyond that, the exact reasons for the murder remain opaque.

One theory posits that Escobedo had discovered Ana and Antonio’s affair and threatened to reveal their secret. He might have also tried to barter his discretion in exchange for their help in convincing Philip to fund his brother’s political aspirations in Flanders (which, to be fair to Philip, were a bit on the wild side and included invading the English, freeing the captive Mary I of Scotland and reinstituting Catholicism in England). Antonio then pre-emptively denounced Escobedo and Juan of Austria before the king, exploiting Philip’s jealousies and insecurities, and got him to give the go-ahead for the assassination.

Some historians suspect alternative — or additional — motives, including a complex scheme on Ana and Antonio’s part against Juan of Austria regarding the succession to the then-vacant Portuguese throne.

While we don’t know for sure who was scheming against whom, what’s certain is that there was scheming galore, and for good reason.

The king’s favour was notoriously fickle. His father had warned him repeatedly to be wary of counsellors since he was a child. That, combined with Philip’s shy and anxious disposition and the great demands of his office, resulted in an almost pathological distrust of even his most loyal advisers. Antonio Pérez and the Princess of Éboli were just two entries in a long list of people once close to the monarch who ultimately suffered disgrace. Philip’s official court historian, Cabrera de Córdoba, summed it up well: ‘His smile and his dagger were very close’.

It’s no wonder, then, if Antonio Pérez saw fit to conspire with and against all parties simultaneously to protect his tenuous position: with the king against Juan of Austria; with Juan of Austria and the ill-fated Escobedo against the king; and maybe even with the Flemish rebels against both.

Antonio must have been mindful, too, of the fact that he was very much disliked by the grandees at court from day one. He was the bastard son of a priest, an upstart and, to add insult to injury, he was smart, talented and in the good graces of the king, at least initially. The chair he sat on was wobbly indeed.

Public opinion immediately blamed Antonio Pérez for the murder, but more than a year passed until Philip ordered his arrest on 28 July 1579 — probably once he realised he’d been tricked into signing Escobedo’s death warrant.

The Princess of Éboli was apprehended later that night as she stood in the street outside her residence with her maid. But, unlike Antonio, she was never formally accused of murder — or any crime, for that matter. Throughout Ana’s 13 years of imprisonment, the Crown didn’t ever press charges or bother with even a semblance of a fair trial. In fact, her direct involvement in the Escobedo murder has never been proven, then or now.

A key fact that’s often glossed over is that the Princess of Éboli had known Juan de Escobedo since she was a little girl. Before his appointment as secretary to Juan of Austria, he’d been a secretary first to Diego de Mendoza — Ana’s father — and then to her husband, Ruy Gómez. He was also a confidante to Ana’s mother, Catalina, who addressed him as ‘cousin’ in her letters.

After Ruy’s death, Ana retained Escobedo as her adviser. We have multiple letters written by the princess to Escobedo. All of them are friendly and personal; in one, she even calls him her ‘pillow’ or counsellor. She updates him on everything that’s troubling her: her health; her eldest daughter’s insufferable mother-in-law. In the words of the historian Trevor J Dadson, ‘These are not the letters you write to someone you are planning to murder’.18

The taming of the shrew

According to Dadson, the Escobedo affair might have been just a pretext for Ana’s arrest. The real reason seems to have been her persistent meddling in state affairs. She had been trying the patience of the powers that be for far too long.

The straw that broke the camel’s back was Ana’s raging, and somewhat puzzling, antipathy towards the other royal secretary, Mateo Vázquez de Lecca.

The official line of the Crown, insofar as any justification for her arrest was given, was that the Princess of Éboli had incited such a high degree of resentment between Mateo Vázquez and Antonio Pérez that it was negatively affecting the workings of government.

Her loathing of Vázquez had become notorious and gone completely out of control by this point. The king himself had asked Ana, repeatedly, to calm down, stop meddling and leave the man alone — to no avail. Philip then tried to use people close to the princess to make her see reason, including Diego de Chaves, the king’s confessor, and Cardinal Gaspar de Quiroga, a close friend of the Ébolis.

She responded in typical Ana fashion by writing a letter to the king in which she called Vázquez ‘that Moorish dog’.19

Interestingly, the bulk of the letter discussed a lawsuit she had against her cousin, the Marquess of Almenara, regarding the inheritance of some of her father’s estates. Things weren’t going well for Ana in court, and she believed she was treated unfairly, among other things, for being a woman and a widow. She also wrote that she suspected the dark hand of Vázquez behind her legal ordeals.

Ana begged Philip to keep her letter confidential and not pass it on to ‘that man’.20 The document was later found among Vázquez’s archives, so the king seems to have ignored her request.

In late July 1579, confessor Chaves made a last-ditch effort to reason with the headstrong princess. We don’t have her letter to him, but we have his response dated two days before her arrest. From it, we gather that Ana had threatened to get Mateo Vázquez removed from court, that she had incriminating evidence against him and that she would make it public. Say what you will about her, but the woman knew how to hold a grudge.

Chaves requested that she pass the evidence over to him, otherwise he’d wash his hands of the whole affair. He implored her to stop her campaign against Vázquez and warned of the gravity of these sorts of threats. Two days later, the princess was arrested.

Then there’s a third letter, possibly written by the Count of Tendilla, a relative of Ana’s, to Mateo Vázquez two weeks after her arrest. In it, the count directly blames Philip II for the whole fiasco. The king’s mistake? ‘Allowing rich widows to run riot around Madrid; litigating in the courts […] without any male control. They should be removed from the capital and sent back to their estates.’21 Not a word on Escobedo’s murder.

‘It is quite likely, therefore,’ Trevor J Dadson writes, ‘that Ana’s arrest was due to her meddling in state affairs and to the fact that, as a widow, she had a freedom that she had never enjoyed as a daughter or wife and she was now using it, to the great annoyance of the king.’22 And many others, it seems.

A walled-in woman

Ana was imprisoned under harsh conditions — unusually harsh for a woman, especially one of her noble stock — and was stripped of most of her belongings and legal rights.

She was initially jailed in the fortress of Pinto outside Madrid for half a year. In February 1580 she was taken to the Santorcaz fortress for a further year, before being relocated to her ducal palace in Pastrana in March 1581.

The Princess of Éboli lived out the rest of her days under house arrest. The conditions of her imprisonment deteriorated after November 1582 and even more so after 1589 when Antonio Pérez broke out of jail, fled to Aragon and started a decades-long and very public campaign against Philip II.

Antonio’s flight resulted in Ana losing whatever measly privileges she’d had until that point. Her papers and possessions were embargoed or sold to pay her debts. Philip had bars installed on the doors and windows of her palace, and she was restricted to living in two small rooms.

There, the princess spent the final 21 months of her life as an emparedada — a walled-in woman. The door to her rooms was replaced by a turnstile, and the only window had bars placed over it. Ana’s only companions were three maids and her youngest daughter, who was only six or seven when her mother was arrested and was forced to share in her 13-year imprisonment.

The barred balcony of Ana’s quarters overlooks a square that is now known as Plaza de la Hora, or Square of the Hour, because the captive princess was allowed to look out the window for an hour each day.

To her credit, throughout all those years she neither confessed nor apologised — for Escobedo’s murder or for anything else. What she did do was fight, relentlessly, for her two goals: to free herself and to salvage her family’s legacy, using the law, her social standing and her connections. In the words of Trevor J Dadson, ‘The most remarkable aspect of Ana’s life in this period is her strength’.23

What puzzles historians is Philip’s disproportionately harsh attitude towards the princess. Ana’s punishment was unusual for a high-ranking noblewoman, especially in the absence of formal charges, evidence or a confession. Antonio Pérez suffered a more bitter fate, including torture, but he’d been charged with (and eventually confessed to) political assassination.

During her imprisonment Ana wrote to the king, addressing him as ‘cousin’ and begging him to ‘to protect her as a knight’.24 For his part, Philip would refer to her as ‘the female’ or ‘the pig’.25

His feelings towards the Princess of Éboli aside, the king did protect and care for her children after her arrest; likely because of their father, his late friend Ruy Gómez, and possibly because of their social standing, too.

Antonio’s wife and seven children — of non-aristocratic birth and with a traitor for a husband and a father — didn’t enjoy such treatment. They were all imprisoned from 1585 until 1598 when Philip II died.

Go out with a bang

The Princess of Éboli died on 2 February 1592 at the age of 51. Her health had worsened significantly during her various imprisonments, likely precipitating her death.

By then, all sorts of wild rumours and legends had grown up around her. Many more were invented over the centuries — including by historians.

But when we do away with the fiction, the real Ana emerges and, ironically, is far more fascinating. To quote Trevor J Dadson again, ‘In her case there is no need to invent anything: the reality is far more rewarding than any fiction’.

The Princess of Éboli lived fast and died young. By the time she turned 39, she’d had nine or 10 children, 20+ years of marriage and possibly one (or two) tumultuous affairs with some of the most powerful men in Europe. She’d survived her abusive parents, lost three or four children and mourned a husband. She’d run vast estates, schemed and plotted at the highest political level and fought for her family’s legacy and her children’s future.

Then followed 13 years of imprisonment, during which she didn’t back down or admit defeat. She stood her ground — doggedly, one might say foolishly, narcissistically even — much like during her stint at the convent and the ill-fated clash with Mateo Vázquez.

Whatever the content of her character and the finer details of her biography, one thing is certain: Ana de Mendoza y de la Cerda was the sort of woman that goes out with a bang.

Phew! Talk about a long read, eh? If you made it to end — thank you so much for your time. Here’s your prize: a cute modern rendition of a delightfully raunchy song from the Spanish Renaissance. Who knows, perhaps Ana and her friends sang it during their feasts.

Dadson, T.J. Ana de Mendoza y de la Cerda, Princess of Éboli. Image, myth, and person. In Roe, J. & Andrews, J. (eds.), Representing Women’s Political Identity in the Early Modern Iberian World (Routledge, 2021) pp. 417-448.

ibid.

Dadson, T.J. The education, books and reading habits of Ana de Mendoza y de la Cerda, Princess of Éboli (1540–1592). In Cruz, A. & Hernández, R. (eds.), Women’s Literacy in Early Modern Spain and the New World (Ashgate, 2011) pp. 79-102.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

Dadson, T.J. Ana de Mendoza y de la Cerda, Princess of Éboli. Image, myth, and person. In Roe, J. & Andrews, J. (eds.), Representing Women’s Political Identity in the Early Modern Iberian World (Routledge, 2021) pp. 417-448.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.