On the fabrication that is Greek and Roman art

Or: colours in Antiquity & why the ancients had no taste

The artworks featured in this post look best on larger screen sizes. To get the optimal visual experience, view this page on substack.com (not in your email) on a desktop or laptop computer.

How often do men think of the Roman Empire? Hardly a question you’d expect to go viral on social media, yet here we are. Women are flooding TikTok with their partners’ responses, while experts like historian Mary Beard have taken the opportunity to bust myths about ancient Rome as a “safe place for macho fantasies”.

Regardless of how often you contemplate the Roman Empire — or ancient Greece, for that matter — visions of ivory temples and sand-coloured amphitheatres likely come to mind. Save, of course, for the occasional chilling yet uncompromisingly tasteful red accent in the form of a legate’s cloak or a blood-spattered wall.

The thing is, this off-white and eggshell-dominated palette, which inspired the pristine surfaces of Renaissance sculptures and the blank facades of Neoclassical buildings, is... a lie.

Or, to put it more nicely, it’s a figment of our collective imagination, wishful thinking that the ancient past was more noble and sophisticated than it really was — or, at the very least, that it was more aesthetically pleasing than the visual cacophony of our modern cityscapes.

Well, that last part may be true. But as far as colours go, I’m sorry to report less wasn’t more in the ancient world.

Antiquity, imagined

It all started in the Renaissance, when a renewed interest in Classical Antiquity fuelled the first systematic efforts to unearth and study Graeco-Roman relics.

Most of these sculptures and ruins were devoid of colour. As a result, generations of scholars and artists came to believe the ancient world was almost exclusively made of white marble, reddish terracotta and patinated bronze.

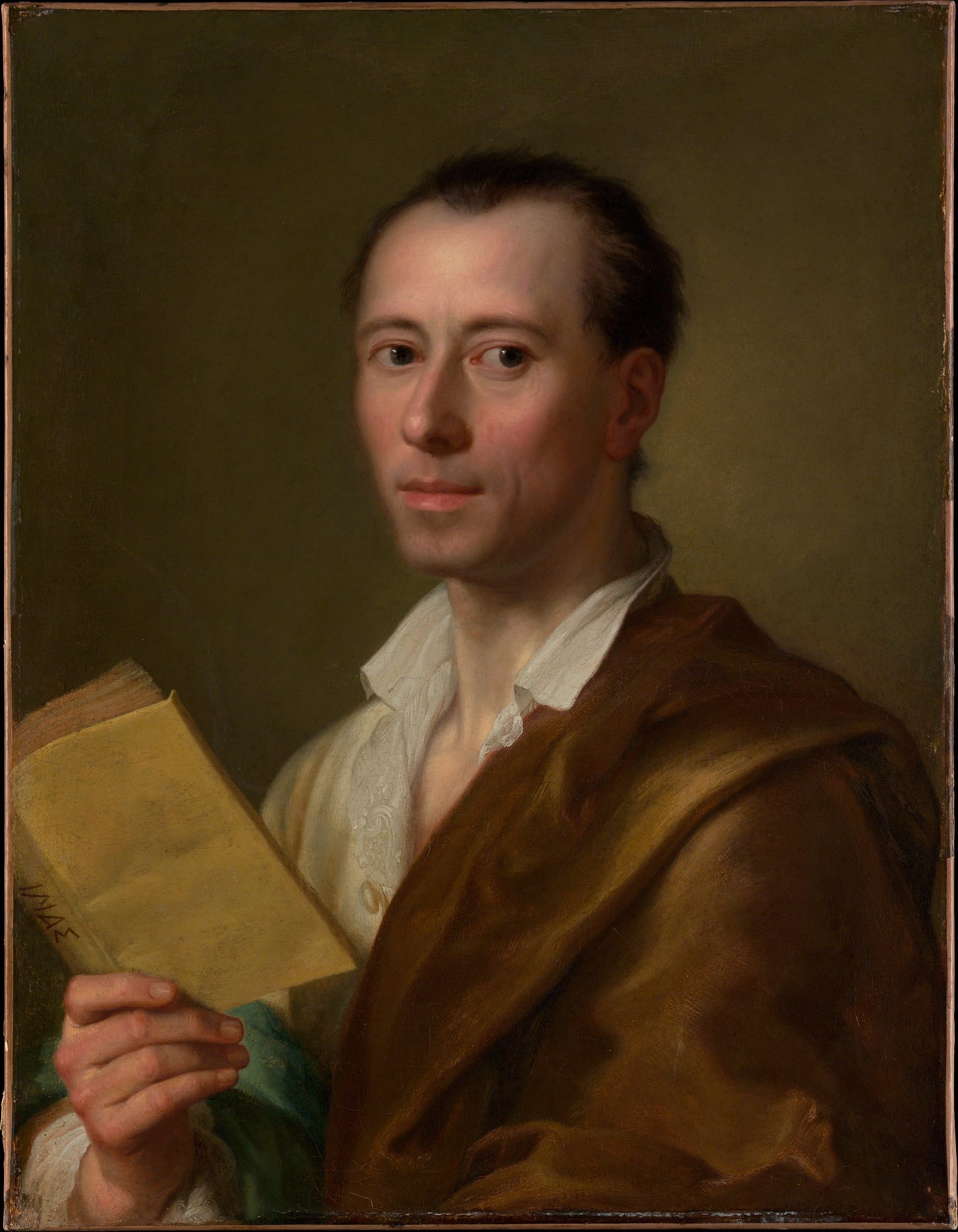

One man in particular helped perpetuate this misconception. Meet Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768), the hugely influential “prophet and founding hero” of archaeology and art history who, among other things, was largely responsible for the intellectual “tyranny of Greece over Germany” in the following centuries.

Winckelmann loved the perceived “whiteness” of Greek sculptures. Today, we might call it minimalism, but he called it — rather more elegantly — “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur”.

It’s not that Winckelmann didn’t appreciate colour or thought white was superior among colours. He rather saw white as an absence of colour. This lack of visual noise allowed “structure” — beauty’s true essence — to take centre stage like an ideal Platonic form come to life.

Colour contributes to beauty, but it is not beauty itself […]. Since white is the colour that reflects the most rays of light, and thus is most easily perceived, a beautiful body will be all the more beautiful the whiter it is […] Colour should have a minor part in the consideration of beauty, because it is not [colour] but structure that constitutes its essence.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, History of Ancient Art (1764)

In his defence, Winckelmann had a lot less material to work with than we do today. He often had to resort to extrapolation and his vivid imagination to fill gaps in the contemporary understanding of ancient Greece and Rome.

Still, it looks like the German scholar engaged in colour blindness at least on one occasion. During a trip to the Mount Vesuvius area in 1762, he studied the recently discovered Artemis of Pompeii, which bore evident traces of colour.

Initially Winckelmann attributed the statue to the Etruscans, who at the time were seen as less refined than the Greeks. Later, he ascribed it to Greece’s Archaic period. Researchers today generally agree that the Artemis of Pompeii is a Roman copy or imitation of a Greek statue in the Archaic style of the sixth century BC.

That remained the prevailing scholarly view on ancient Greek polychromy for a long time — if it did exist, it was surely a remnant of a more primitive culture, an unfortunate lack of taste in the evolution towards the civilisational pinnacle that was monochromatic classical art.

It is also worthy of remark, that savage nations, uneducated people and children have a great predilection for vivid colours; that animals are excited to rage by certain colours; that people of refinement avoid vivid colours in their dress and the objects that are about them, and seem inclined to banish them altogether from their presence.

Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Theory of Colours, 1810

A colourful awakening

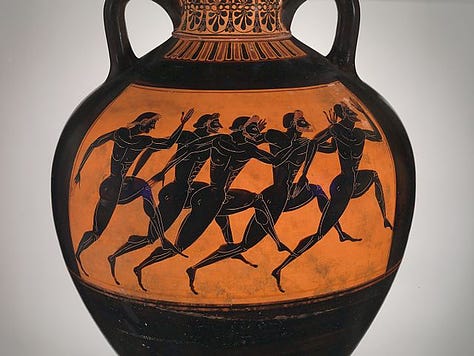

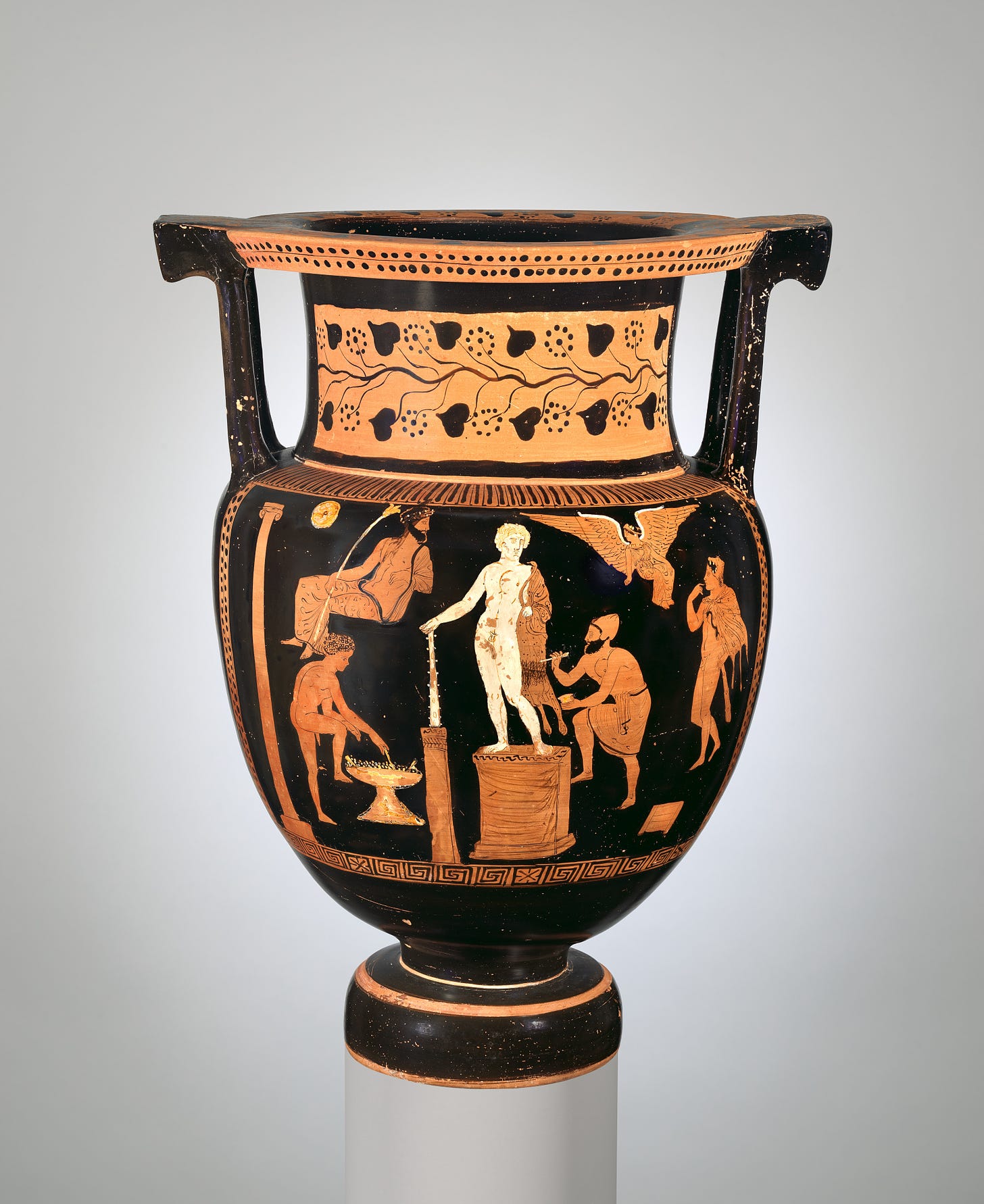

As time passed, it became impossible to ignore the growing number of Greek and Roman relics with colour traces that kept turning up. Secondary evidence, such as literary sources and images on ancient vessels, also refers to painted sculptures.

My life and fortunes are a monstrosity,

Partly because of Hera, partly because of my beauty.

If only I could shed my beauty and assume an uglier aspect

The way you would wipe colour off a statue.

Euripides, Helen, 260-263

In the 19th century, ancient polychromy started gaining acceptance, but interest in it plummeted in the 20th century. Fast-forward to the early 21st century, modern technology and science have given us much broader insight into colour in Antiquity.

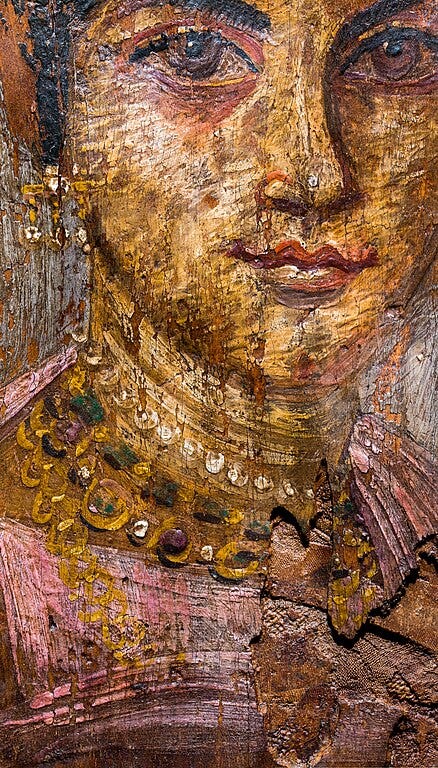

We now know the ancient world was steeped in colour. Sculptures were once ornately painted. They merely appear white because most of the paint has worn off after millennia of weathering and soil accumulation.

Human activity has also caused damage. People would wash and scrub relics that came dirty from the ground, destroying what little was left of the original paint.

But it wasn’t just sculptures that were colourful: The streets of ancient Greece and Rome were lined by brightly painted buildings. As if that weren’t enough, coloured graffiti would often adorn the facades.

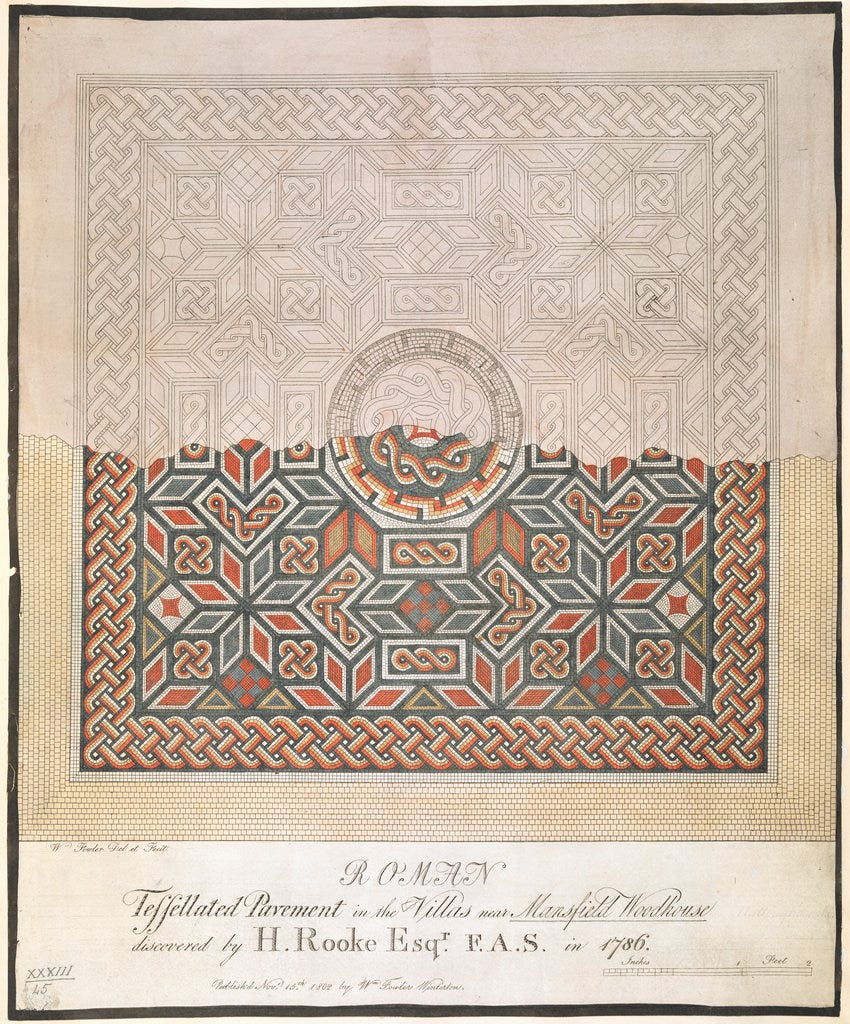

Indoors, wealthy Romans would pay a small fortune to have every square inch of their walls covered in frescoes and their floors lined with colourful mosaics. Even everyday objects like bowls and cups were bursting with colour, and people commonly wore brightly dyed clothing.

Antiquity, reimagined

Today, archaeologists and artists use modern technology to create hypothetical reconstructions of ancient relics.

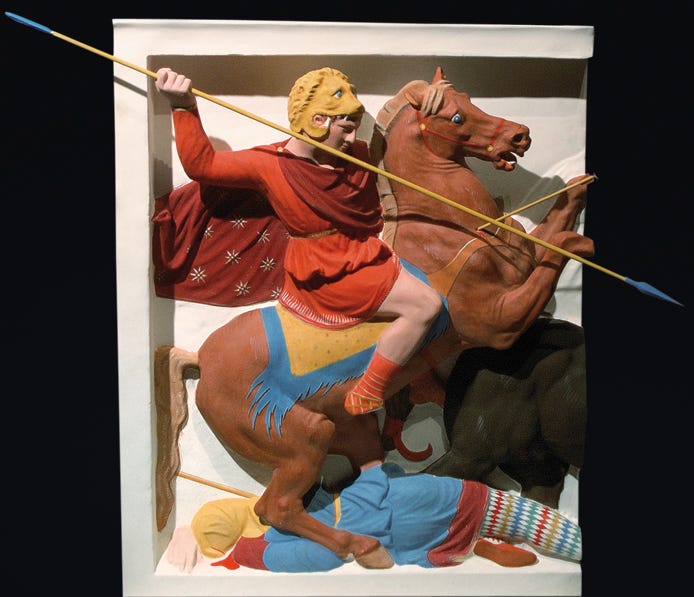

German archaeologists Vinzenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann have spent decades trying to revive the colours of ancient Greece.

Using cameras, UV light, high-intensity lamps and powdered minerals, they have created plaster or marble copies of well-known ancient artworks. The meticulous full-scale reconstructions even feature the same minerals and organic pigments Greek artists would have used.

The results are rather startling and may even be perceived as an affront to good taste from our modern standpoint, but nothing suggests they are historically inaccurate. Feast your eyes:

Still, it’s hard to get a proper feel of the ancient world in all its glorious peacockery through reconstructed statues alone.

For a larger-scale perspective, check out the work of Hungarian 3D artist Ádám Németh. His virtual renderings of historical buildings and artefacts include stunning reconstructions of ancient sites like the Nymphaeum Traianus and Curetes Street in Ephesus, Turkey.

While visually impressive and thought-provoking, these kinds of projects are few and far between. It remains to be seen whether they will successfully challenge our deep-rooted (and cherished) misconceptions about what the world of Classical Antiquity might have looked like.

The vision of a noble monochromatic past, while fabricated, still holds powerful sway over our collective imagination. As classical scholar Alfred Emerson put it in 1892:

[…] so strong was the deference for the Antique, learned from the Italian masters of the Renaissance, that the accidental destruction of the ancient colouring [was] exalted into a special merit, and ridiculously associated with the ideal qualities of the highest art.

I'm glad we've realized the statues were painted, I just wonder why no one talks about the theories (and they must exist out there) that the Greeks and Romans also used paint to exaggerate and create light, shadow, dimension, and depth. Basically; I doubt they just flatly painted on some colors and called it a day. That feels like a great underestimatation of their skills. Especially considering the skill with it that the images or the portrait, fresco, and bedroom show in this article.

Just feels... Like of course a beautiful statute flattened with paint looks garish and like too much to us today. I doubt the sculpter would just flatten all their work like that.