As if there isn’t enough turmoil in the world, two Just Stop Oil protesters were arrested last week after smashing the glass protecting the iconic Rokeby Venus by Diego Velázquez at the National Gallery in London.

The daring feat of attacking a defenceless artefact — I wouldn’t call it an inanimate object because I’m not at all sure that’s the case — isn’t just counterproductive to the green cause. You see, that could be forgiven.

The trouble is, this form of protest is also profoundly and exasperatingly unoriginal and intellectually feeble, and that — considering the activists’ lofty rhetoric — is indefensible.

Let’s go over a non-exhaustive inventory of people who have targeted artworks for ostensibly noble political purposes and examine some proposed psychological motivations for those attempted articides (if that’s not a word, it should be).

Then, in next week’s post, we’ll delve into a far more interesting subject: the fascinating story of The Rokeby Venus and why this painting, like all great art, is in itself a form of quiet protest more subtle and sophisticated than anything the likes of Just Stop Oil will ever muster.

True crime: The museum files

Last week’s incident was drearily predictable. The Rokeby Venus affair comes hot on the heels of several widely publicised attacks against artworks by climate activists.

Other high-profile London-based victims include Van Gogh’s Sunflowers and a copy (mercifully) of Da Vinci’s The Last Supper.

Further north, Edinburgh Castle was shut down on 15 November after activists smashed the protective case containing The Stone of Destiny, used for centuries in the inauguration of Scottish and later British monarchs.

Across the Channel in The Hague, we had the particularly cringe-inducing incident involving Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, a bald guy and a can of tomato soup. I honestly don’t get why he couldn’t just glue his hand like everybody else.

None of this is new or original, of course. Political activists — as well as religious fundamentalists and mentally ill people, but those merit a separate discussion — have been targeting works of art since forever.

To name just a few examples, in 1974 a Japanese woman, Tomoko Yonezu, tried to spray-paint the Mona Lisa, which was exhibited in the National Museum in Tokyo, in protest of the museum’s crowd control measures that disability activists deemed discriminatory.

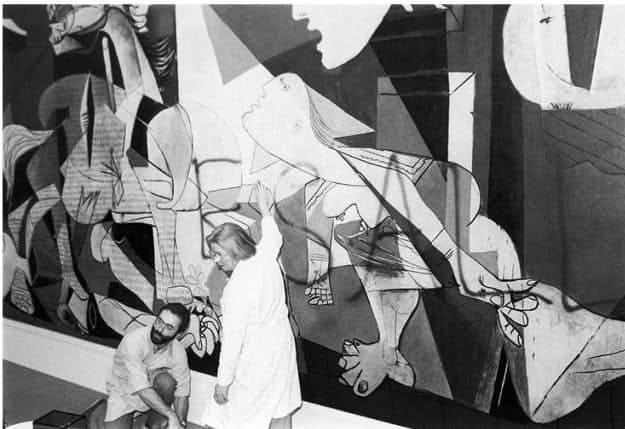

That same year, art dealer Tony Shafrazi stormed into the Museum of Modern Art in New York and spray-painted “KILL LIES ALL” on Picasso’s antiwar painting Guernica. Shafrazi was protesting President Nixon’s pardon of William Calley, a US Army officer who had been convicted for the 1968 My Lai Massacre during the Vietnam War.

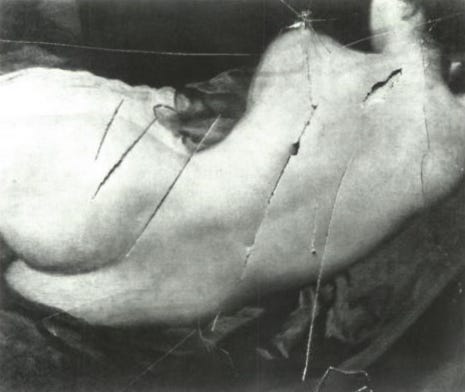

This isn’t The Rokeby Venus’s first time around the block, either. On 10 March 1914, the Canadian-born suffragette Mary Richardson slashed the 17th-century canvas with a… meat cleaver (!) provoked by the arrest of fellow suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst.

The painting was badly damaged but later fully repaired by Helmut Ruhemann, the National Gallery’s chief restorer.

But why?

Some justifications for activist art vandalism are better reasoned than others. Spray-painting antiwar slogans onto a famed antiwar canvas, like Tony Shafrazi did with Guernica, certainly makes sense.

Mary Richardson was as controversial a figure as they come (she later became head of the women’s section of the British Union of Fascists), but at least her reasons for slashing The Rokeby Venus were consistent with her feminist ideology:

I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government for destroying Mrs Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history. [...] If there is an outcry against my deed, […] such an outcry is an hypocrisy so long as they allow the destruction of Mrs Pankhurst and other beautiful living women, and that until the public cease to countenance human destruction the stones cast against me […] are each an evidence against them of artistic as well as moral and political humbug and hypocrisy.

“Miss Richardson’s Statement”. The Times. London. 11 March 1914.

In another interview Richardson added, with surprising candour, “I didn’t like the way men visitors to the gallery gaped at it all day”.

But what of our modern-day climate activists? The Just Stop Oil protesters who targeted the same painting last week called on the UK government to end all new oil and gas licences and take drastic climate change action. In their own words:

Women did not get the vote by voting. It is time for deeds, not words. It is time to Just Stop Oil. Politics is failing us. It failed women in 1914, and it is failing us now. New oil and gas will kill millions. If we love art, if we love life, if we love our families, we must Just Stop Oil.

The duo also broke the safety glass using emergency hammers because the world is in a climate emergency.

They may have a point, but why target an artwork that’s not even tangentially related to their message? How does the suffragette movement pertain to the green cause more than any other historical social justice movement?

Last year, Just Stop Oil supporters attached an “apocalyptic vision” to Constable’s The Hay Wain, which depicts an idyllic scene in rural Suffolk. Now, that makes sense or at least is intellectually congruent.

Left: John Constable, The Hay Wain (1821). The National Gallery. Right: Two protesters glued onto the frame of The Hay Wain at the National Gallery in London. Image source: Just Stop Oil But why target artworks in the first place? It can’t be for publicity alone. Other forms of protest could draw just as much media attention and may even be better at effecting real-world change.

Artists and art lovers tend to hold left-leaning political views anyway, so protesters splashing soup in museums and galleries are not only preaching to the choir but risk alienating the very people who support them.

Some men just want to watch the world burn

Recent psychological research points to deeper, more sinister motivations behind the destruction of art and beauty.

Take this article from the April 2021 issue of The Royal Society journal. The authors analysed data from large-scale surveys conducted in Australia, Canada, the UK and the US, identifying the prevalence of what they dubbed a Need for Chaos.

“Some men just want to watch the world burn”.

— The Dark Knight

Political observers and scholars are sounding alarms over increasing polarization between political parties, the emergence of populist movements and leaders, the circulation of misinformation, hostile interactions on social media and rising levels of actual political violence.

While traditional forms of political activism in Western democracies focus on winning power and support through conventional means provided by the political system, these emerging forms of activism seek to disrupt the existing system altogether.

As Alfred the Butler, a character in The Dark Knight, explains in the quote above, some people want to tear down existing social and political institutions rather than build them.

According to the authors, while there may be a link between disruptive activism on the one hand and social marginalisation and economic inequality on the other, not everyone who feels marginalised wants to “watch the world burn”.

A growing body of research indicates that these “highly disruptive sentiments” — the Need for Chaos — are contingent instead on something else: an intense desire for social status.

Individuals vary in the degree to which they crave status and, when excluded, individuals who possess an intense desire for status are more likely to view disruption and chaos as a viable strategy for obtaining the status that they crave. Accordingly, status-obsessed yet marginalized individuals may find it more attractive to disrupt the entire social hierarchy altogether rather than to engage in a slow, seemingly futile climb up the social ladder.

The article further posits that the Need for Chaos is highly correlated with personality traits such as the Dark Triad of Machiavellianism, Psychopathy and Narcissism.

Across all four Anglo-Saxon countries, most people fall in what the authors dub the Low Chaos category, but around 20% support some degree of chaos-seeking.

I’m no psychology expert, of course, so I can’t comment on how well this study has been conducted or how it fits in the broader context of extant and emerging research — but the article certainly provides ample food for thought.

That’s it for now. If you made it to the end — thank you! — and I hope you enjoyed it. Stay put for my next post, in which we’ll examine a far more appealing subject: The Rokeby Venus herself.

We’ll look into her enigmatic story, her even more enigmatic message and the many ways in which she represented a major departure in European and Spanish art (and certainly Spanish morals). Hasta pronto!